My career in education started as an 8th-grade science teacher in a school district in West Texas. For 9 years I lived the life of a classroom teacher with my eye on growing professionally. I taught a STAAR tested subject, got my Master’s degree, launched a middle school STEM program, and eventually got the opportunity to become a content coordinator in a neighboring district.

One thing that was consistently an issue throughout those 9 years was the wild fluctuations I’d see in classroom observations and walkthroughs between a variety of evaluators. It was perplexing as, from time to time, similar types of lessons (different topics, of course) would be observed, and scores and feedback would vary from evaluator to evaluator.

Now, you might ask for a second…why didn’t I adjust my lessons based on the feedback? There was very little to adjust. It was never negative, and I was doing things that the evaluators approved of, but it was still inconsistent. This vexed me.

After a couple of years as a content coordinator, I became a director and, like many of you, became a wearer of many hats. Among those responsibilities, I was charged with managing the teacher evaluation system for the district. Over time, I helped identify gaps in evaluation practices using evaluation data. So the question became, how do I align all of our leaders so that no matter who goes into a classroom, the teacher could expect a pretty reliable and realistic evaluation of their performance?

Evaluate the Health of Your Evaluation System

The journey to aligning every teacher evaluator in the district had to start with figuring out just how healthy the system was. I had to identify questions and then find the data I needed to answer them. Some of the questions were obvious: How consistent are the walkthroughs and evaluations between evaluators on each campus? How much evidence is included to justify particular ratings?

Other questions were less obvious and required a little reading. Digging through a variety of resources, including the Education Resource Information Center (ERIC) and Edutopia, I was able to find a few additional things that helped point me in the right direction.

- What is the purpose of teacher evaluation?

- What does instruction look like at each of the proficiency levels in the rubric?

- How do we know we’ve seen something that is or is not effective?

- How are we involving teachers in the evaluation process?

Identifying the Need

With my questions lined up, I had to dig into the data to find some answers. Digging into evaluation data required a deep dive into all of the summative, observation, and walkthrough trends I could get my hands on. Luckily, we used Strive which kept all of our data in a place that I could comb through it and generate some reports.

In working with Strive’s Document Summary feature, I found out pretty quickly that our first need in the district was to have a singular, comprehensive walkthrough document. Every campus had its own versions and we had no easy way to analyze trends across the district. I’ll speak a little later about working to find a common template that can be used for proper analysis. Luckily, the observation and summative rubric had what I needed, so I got to digging.

District Averages

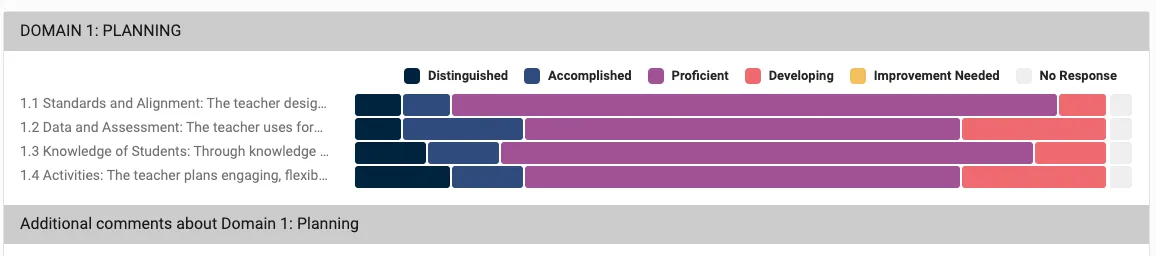

Right away I was able to pull up a graphic that showed the district trends on our observations for all of our teachers throughout one school year. At a glance, I was able to quickly see a very high trend towards accomplished and proficient scores across all domains. There was a heavy skew to one end of the rubric. That’s not enough to draw conclusions about reliability, so I had to dig deeper. So, I pulled two middle schools and put them side by side.

When I pulled the individual schools, a trend began to emerge.

School 1

School 2

Do you see it? School 1 was very different from the district averages, leaning more heavily toward proficient scores. They looked a lot like a normal bell curve might look. Meanwhile, School 2 was in line with the district averages. So who was doing it better? How likely is it that the teachers at one campus are that much better than at the other?

It occurred to me that it was very unlikely that the teachers performed that differently across the two campuses. The STAAR performance data didn’t reflect such a significant difference. After a lot of reflection, it also occurred to me that it didn’t matter who was doing it “right or wrong.”

What mattered first is that we had to achieve some consistency and we had to make the focus about improving instruction. These graphics were going to help me set the stage to show that teachers at one campus can do things exactly the same way as another and get extremely different results on their evaluations.

Finding the “Why”

The next step required that I get all evaluators in the district on the same page as to why we do evaluations on teachers (National Council on Teacher Quality). But first, I had to find the answer for myself.

There’s an obvious answer: We do evaluations to make sure teachers are doing what they need to do to make students successful. But that’s too generic. It lacks a strong hook into why we need to do it effectively.

Evaluator’s lives are incredibly busy. In 2017, it was reported that a typical school principal spends less than a fourth of his or her time in classrooms (ERIC). Managing a building is very time-consuming and without an appropriate effort to prioritize teacher evaluation, it becomes too easy to let evaluations take a back seat. It becomes something to just get done as quickly as possible.

If we all align on the importance of investing the time needed to evaluate teachers effectively, we have a common ground to reference when moving forward.

I found through a vast landscape of education research that teacher quality is positively linked to student learning. These resources on feedback and evaluation systems proved especially helpful when forming this conclusion. Therefore, investing time into growing and supporting quality teachers is an investment in student learning.

A number of things speak to teacher quality, including but not limited to:

- experience

- classroom environments conducive to learning

- creating positive relationships with students and staff

- effective use of assessment and instruction

- planning

- differentiation

- communication of expectations

- collaboration with colleagues

- participating in quality professional development

Of all of those things, all but one of them (experience) can be evaluated in most teacher evaluation rubrics across the country. Effective, healthy evaluation systems carefully look into each of those components and provide meaningful feedback to ensure that teachers are being fueled by what they need to grow or to perform at high levels.

At the end of the day, despite the bad taste it can leave in the mouth, another reason to invest in a quality evaluation system is accountability. This feels a little gross to even mention because accountability is inextricably linked to state-level testing. State-level testing shouldn’t be a driving force for change. But the reality is that the education landscape has been molded over the last several decades to point towards state testing numbers at every opportunity. Having a strong evaluation system in your district will lead to improved accountability as teacher quality is reinforced and instruction improves over time.

Finally, after all of my research, I had it. Our “why” was going to be that “teacher quality is driven and sustained by quality evaluation practices.” When teacher quality increases and stays high, many problems in our buildings can solve themselves. An effective teacher evaluation system is the best way to achieve that.

Align on the Importance of Reliable and Consistent Teacher Evaluation

The next step was to paint the picture that effective teacher evaluation systems solve other problems for our evaluators. There are a number of ways to do this, but I found it was easiest to get all of the principals in one place and talk about it all at one time. My district had a standing principal meeting each month which served as the best opportunity. It also provided a great forum for questions and communication.

To start the conversation, I prepared all of the data I had available for them. I prefaced the conversation with the data, then asked them to explore it and record any thoughts or questions that they had. I let the principals work in campus teams to look over the information. It was all reasonably anonymous, but each administrator team was able to identify which set of data likely belonged to them and could see differences across each. It was easy for them to conclude that something was off. Every campus had some level of skew when compared to the district averages.

They saw the need for change without me having to tell them, “Hey! We need a change.” This revelation enabled us to have a great and honest conversation about the need to align, explore some best practices, and really explore reliable and consistent evaluation systems that would naturally guide the instructional changes they were desiring from their teachers.

Principals really can be drivers of improved student achievement by leveraging feedback and evaluation cycles to help teachers grow (National Council on Teacher Quality, 2022). Once the “why” was identified, every principal agreed this was something worth investing in.

The next steps were harder.

Now I had to get them to agree on what instruction looked like in each domain at each proficiency level, and I had to get them to trust the process rather than their feelings.

Aligning on the Method

Now, we’ve identified the need. We’ve gotten the administrators on board. They know that we need to do something. But what do we do? We have to achieve a consistent evaluation process by achieving inter-rater reliability and removing evaluator bias. We had to make it so that no matter who came into your room on any given day, you’d receive a set of scores and feedback that would be very consistent (within an acceptable range).

Achieving Inter-rater Reliability

Inter-rater reliability is a concept that applies the principle of producing consistency on teacher evaluations (ERIC). When a teacher has similar results no matter who is judging the criteria, inter-rater reliability is achieved.

Remember the walkthrough document from before? Now was the time for me to bring that up with the principals. I was able to get the principals to work with me in a workshop-style mini-development to create a common walkthrough document together. Each campus had a different walkthrough because they had different initiatives: Fundamental Five, Marsha Tate, and PLCs at work.

Through our conversation, we were able to identify the key pieces of instruction that they all had in common and create a unified walkthrough document that aligned with the evaluation rubric, not necessarily the program or protocol they had adopted. We were able to take it back to the roots. They could use and keep their protocols, but what was the purpose of the walkthrough? It’s not compliance for using a piece of a strategy. It was about identifying behaviors and interactions that make instruction great.

I took back the results of our workshop and I made a common walkthrough template for every campus. Strive made that pretty easy by allowing me to create a brand new walkthrough document through the evaluation templates. This common ground would help us have conversations later in the year with a wider range of data instead of relying solely on full-period evaluation or observation templates. More, smaller bits of data can lead to richer conversation and exploration of ideas.

We were starting to get onto the same page. By now we’d had two different meetings and achieved two different things. We identified our need and our why, and we created a common walkthrough document.

The next piece was to create and deliver an actual system that could create interrater reliability. The best way to do that is to get evaluators in the same room, watching the same teachers, and sharing notes. But the data was off enough that we had to start more broad than that.

Going straight into your own teacher’s classrooms could get too personal too quickly. Thoughts of defending their staff rather than engaging in honest conversation could overturn the apple cart before we got to our destination. So, we did mass evaluations of lesson videos provided by the state. Texas provides registered principals access to training videos for this exact purpose.

We were able to set up a time to get our principals in one place and watch a 30-minute lesson. Principal groups were broken into elementary and secondary. We all watched the lesson together, wrote our evidence, and then took the time to score the lesson.

Through a collaborative approach, we got our principals to communicate why they selected specific scores. But here’s where I hit a wall, and it’s something you can learn now for when you try to implement this in your district: I didn’t coach the principals ahead of time about really diving into the evidence to justify scores.

I heard a lot of “I think” and “I feel” when it came to assigning scores. Luckily, it was a quick redirect to turn the tide on the conversation, but something came to light that I needed to get addressed–evaluator bias.

Addressing Evaluator Bias

Overcoming evaluator bias required a system-wide approach to having large conversations that eventually lead to small coaching opportunities. Often, evaluators aren’t inflating teacher evaluations because they have some ulterior motive to make their campus look better. It comes from unconscious biases that can be corrected if revealed and discussed..

Sometimes, a lack of alignment on a teacher’s evaluation lies in the emotions tied to the person. Teachers and principals are people. They build relationships, they learn to live with and sometimes even like each other. Those relationships sometimes create a barrier to, or a lensing effect on, seeing what’s happening in a classroom. This bias became known as the “I think, I feels [sic]” effect in my district. We would refer to it often when having joint conversations and sometimes even ask, “Are you leaning into the ‘I think, I feels’? Or are you looking at the evidence?”

This may look a lot different in your district, and you need to take your district culture into account when dealing with these biases. In some cases, the bias may extend beyond personal relationships and dive deeper into issues that are harder to address such as gender or culture bias. If you find biases that are linked to something more serious than not wanting to hurt a teacher’s feelings, take the time to dig into that and have honest conversations with the specific evaluators you’re analyzing.

In my district, the whole group evaluation experience opened doors to conversations and opened minds to reinforce our needs and our why. The principals were ready to have small group evaluations on their campuses with their teachers.

Coaching and Follow-through

Like any teacher coaching process, coaching is a valuable tool when working with evaluators in a district as a way to follow-through, provide feedback, and address long-term interrater reliability (Georgia Department of Education). Over time, people can regress to old habits. Scheduling time to go into classrooms and do joint observations helps to keep everyone on the same page, and that’s exactly what we did.

In my district, we developed a system where principals were to schedule a time periodically to go and do joint teacher walkthroughs. They’d visit 3 to 4 classrooms on their campus together, then sit down to have a shared debrief on what they saw and how they would score the walkthrough. As needed, a district teacher evaluation coordinator would join these principal teams and participate as well. These conversations helped principals hold each other accountable for what was expected when going into the teacher's rooms.

We added another layer of interrater reliability checks when once a year, each evaluator would do a full teacher observation with another evaluator as a cross-check. We would set up a virtual sign-up so principals could do these across campuses. We found this strengthened interrater reliability because evaluators were able to tap into people outside of the group they worked with most closely.

Follow-ups also allowed a gradual introduction to meet and fill other gaps in practice, including documenting evidence for scores and ensuring the principal and teacher were able to sit and have the required conversations. Any evaluation process is only going to be as strong as the feedback and growth that come from the conversations occurring around the evaluation. These steps were sometimes harder to implement than just achieving interrater reliability, and I’d love to go deeper into that in a later blog.

Taking it further

After a full year of aligning and evaluating, I was able to revisit the entire process and look at the data again. Trends were looking far more consistent at the school level. My next adventure would dive into trends across grade level groups, subjects, appraisee types, and even individual appraisers.

Revisiting the process allowed the district to see some specific data that showed once we achieved interrater reliability at a high level, there were consistently low and consistently high scores in specific subject and grade level combinations. What did that mean? After some hard and honest conversations, it became clear that there may have been some inequity in how teacher talent was distributed. We were able to take that revelation and come back to our why - great evaluation and feedback systems can lead to better instruction.

Achieving a reliable and unbiased teacher evaluation system in your school can be a challenge. But it is a challenge worth accepting, especially when you have the right tools to accompany you. Dive into your evaluation data using Strive’s Analysis and Reports. Find the trends, print reports, and begin having conversations. Align your processes and create evaluation templates that can create common ground for comparison and analysis. Revisit Strive regularly to monitor the evaluation process for the entire district and for each individual school. Principals can do this as well for their own campuses. Empower them and train them to use the tools themselves so they can hold themselves accountable.

Check out our resources on using Strive Analysis and reports:

Check out our Overview online help guides:

https://support.eduphoria.net/hc/en-us/articles/4421905912343-Using-the-Document-Summary-Feature

https://support.eduphoria.net/hc/en-us/articles/4408804267159-Create-a-New-Evaluation-Template

Want more help: Reach out to support@eduphoria.net and they can help connect you with training options to get trainers straight to your district and start the entire process with you.

.webp)

.png)

.webp)

.webp)